Friday, July 11, I woke before dawn and drove to Rochester, Minnesota, for an appointment at Mayo Clinic. The scans from a couple of months ago showed spotting on my lungs, and both medical teams in Mankato and Rochester agreed that further imaging was needed to guide how I should move forward with my cancer diagnosis.

Anticipating delays from parking and construction—inevitable around the sprawling Mayo campus—I arrived early. Very early. Like international travel, I’d rather sit and wait than scramble through confusion and stress. That instinct paid off. Because I was early, I was seen early. The pulmonary lab tests, CT chest imaging, and electrocardiogram (ECG) all moved ahead of schedule. A small win. I even had time for a short break, ate an early 10:30 a.m. lunch, and a few deep breaths before the next round: more tests and blood draws, and consultation with my surgeon.

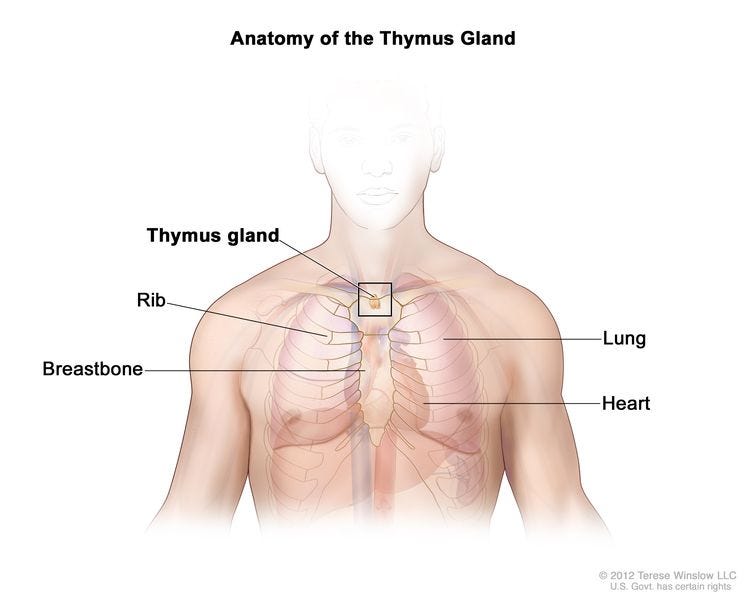

Though I’ve casually said, “I have lung cancer,” that’s not quite accurate. The correct diagnosis is thymus cancer—a phrase that likely prompts the same puzzled look I first gave when I heard it. Not to be confused with the thyroid, the thymus is an entirely different, mostly forgotten gland.

So, let’s talk about this little mystery organ.

The Thymus: A Brief Anatomy of My Companion

The thymus is a small gland tucked behind the breastbone, just above the heart, nestled in the mediastinum—the space between the lungs that also houses the heart, aorta, trachea, esophagus, and several lymph nodes. It doesn’t draw much attention unless something goes wrong.

In its prime—mostly before birth and through childhood—the thymus is the training ground for T-cells, a special type of white blood cell that helps our immune system fight disease and infection. By the time we hit puberty, the thymus begins to shrink, gradually replaced by fat, its job mostly done. But mine, it seems, had unfinished business.

Thymic cancers are rare. There are two main types: thymoma and thymic carcinoma, both arising from the same epithelial cells of the thymus but behaving differently. Thymomas tend to grow slowly and resemble normal thymus cells. They rarely spread beyond the gland. Thymic carcinomas, on the other hand, are more aggressive, more unpredictable, and harder to treat. About one in five thymic tumors is a carcinoma. It is believed I have a thymoma versus the more deadly thymic carcinoma. (We will know more once it is out and is tested in a laboratory.)

My doctors are still navigating what exactly my tumor is, how far it has spread, and what stage I’m facing. So far, they believe it hasn’t traveled far, but more imaging and time will tell. It turns out that the tumor—this slow, shadowy tenant nestled in my chest—has been with me for a long time.

They believe it’s the slow-growing variety, likely a thymoma, not because of some hunch or miracle of intuition, but because of a scan taken eight years ago. That’s correct, eight years ago. That’s when I was hit by a car, and everything in my body screamed out in pain. My sternum was shattered in eight places. My lungs were heavily bruised, and one collapsed. I lost the use of my legs. My dominant arm was heavily bruised and was very painful to use. Glass embedded itself into my face and scalp like a cruel mosaic. My face was reconstructed. The medical teams then were understandably focused on my life-threatening trauma— multiple surgeries, breathing, triage of pain, and body function.

No one considered cancer. Why would they?

But now—years later—Mayo’s current team, digging into my recent Gleason 6 prostate diagnosis and scanning for possible metastasis, stumbled upon the spotting in my lungs. With fresh imaging, they located the tumor in my thymus. And then, like detectives working backward through time, they revisited that old chest scan—the one from the car accident—and found it. Smaller then, but present. Quiet. Waiting.

A slow-growth tumor doesn’t make it less real, less dangerous, or less daunting. But it makes it… known. Traceable. And in some strange way, companionable. It’s been part of my story far longer than I realized.

This is one more reason why regular check-ups are not just prudent, but potentially life-saving. If I hadn’t been scanned now, in light of the prostate diagnosis, the growth on my thymus might have remained undetected until it chose to shout, rather than whisper.

I’ve often said that trauma lives in the body, not just as scar or memory, but as cellular history. The accident eight years ago marked my body permanently. I still carry reminders of that day in my movement, my pain thresholds, my chronic pain in my neck and spine, and in the smallest of tasks I approach differently now.

But that scan—buried in some digital archive, mostly forgotten—held more than evidence of broken bones. It held the beginnings of this current diagnosis. My body has been trying to tell this story for a long time. We just didn’t know how to listen then.

What grace, then, that we’re listening now.

It makes me wonder what else we carry, unspoken and invisible, waiting for the right interpreter. It also makes me marvel at the quiet strength of survival. For all the wreckage of that accident, my body kept going. It harbored a hidden tumor and still managed to heal, to move, to celebrate, to travel, to hold joy.

Sometimes I think of my body as a cathedral (scripturally, the body is your temple)—damaged by time but still housing light. When the hour calls, listen. The thymus is speaking to me, even if it has been silent since adolescence.

What Comes Next

Most people with thymic tumors have no symptoms. The tumor is often discovered by accident, like mine, found during a scan for something else. When symptoms do appear, they can include a persistent cough, chest pain, hoarseness, shortness of breath, or swelling in the upper body. I’ve had some of these, but they’re subtle—easily missed or misattributed. I blamed mine on “old age” of the body beautiful.

As for staging, that’s the next chapter. Whether it’s stage I or IV, the questions are the same: Has it spread to nearby tissues? Has it moved through the lymph system or blood to distant parts of the body?

My treatment will involve robotic surgery—removing what they can see—and possibly radiation afterward, to eliminate any microscopic cells hiding in the margins. This is called adjuvant therapy. My surgeon, Dr. Stephen Cassivi, believes he can get it out in one full swoop. While there are clinical trials, I’ve been encouraged to consider participation if the path forward becomes unclear, but I will deal with that post-surgery and post-cancer check-ups for two years.

In the midst of uncertainty, one thing has brought me great peace: I feel very confident in my surgeon. Dr. Stephen D. Cassivi, MD, is a thoracic surgeon and the vice chair of the Department of Surgery at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. When I met him, I was struck by a rare blend of precision and humanity. His calm was not performative. It was practiced. Grounded. The kind of calm that comes from years of experience and a life dedicated to healing what most of us don’t even realize exists inside us.

Dr. Cassivi specializes in minimally invasive surgical techniques for complex thoracic conditions—lung cancer, esophageal cancer, achalasia, myasthenia gravis, and thymic tumors like mine. His resume reads like a masterclass in excellence: a graduate of the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine, over 15 years at Mayo, more than 250 scientific papers to his name, and a speaker on stages around the world on surgical quality and patient safety.

But what matters most to me isn’t the volume of his achievements, it’s his attentiveness. The way he explained things without rushing and making sure I had a grasp of my condition. The way he made space for my questions and concerns, not as interruptions, but as necessary steps in our shared work of care.

His research includes surgical outcomes, machine learning diagnostics, and remote monitoring. In some ways, he’s helping shape the future of medicine. But in this moment, he is also shaping my future. I trust his hands. I trust his mind. I trust that when I go under, I’ll wake up on the other side of something repaired, something removed, something that’s been silently growing inside me for years.

It takes a kind of spiritual surrender to let someone cut into you, not out of fear, but out of hope. Dr. Cassivi has made that surrender easier.

I left Mayo not with answers, but with momentum. I was reminded that knowledge is a kind of fuel—sometimes overwhelming, but grounding. Knowing where the thymus lives, what it does, and how it can misbehave gives me a strange kind of comfort. It’s no longer an unknown word scribbled on a report. It’s part of me. A quiet companion turned problem child.

And now, I wait. But I wait, informed. And that, too, is a kind of power.

In this season of uncertainty, I am learning that healing doesn’t always arrive with trumpets or fanfare. Sometimes it comes in the form of old scans, specialists, and the steady voice of a surgeon who knows where to cut and when to let the body speak for itself.

I do not yet know the full extent of the path ahead—how long, how winding, how steep. But I do know this: I am not walking it alone. I am held by memory, by community, by science, and by grace.

The tumor in my thymus may have been with me for eight silent years, but it no longer hides. It has a name now. It has a plan. And I have a team of doctors, friends, and unseen forces guiding me forward. Just as I have done in quiet corners of the world, I light a candle and offer what I can: a prayer, a breath, a step forward.

This chapter is not an ending. It is a reckoning. A reckoning with what I’ve endured, what I carry, and what I now release—trusting that the Creator who saw me through shattered bones and embedded glass is still at work in the quiet center of my chest, shaping healing one breath at a time.

This beautiful essay reminds yet again of my mantra throughout my current cancer journey: “I don’t know what I don’t know!” What I do know is that I have the utmost gratitude to my BE doctor for sending me to Sanford Health in Sioux Falls and I have the highest confidence in every one of the medical professionals there who have become my care team!